© 2025 MJH Life Sciences™ , Patient Care Online – Primary Care News and Clinical Resources. All rights reserved.

A History of Aspirin in Modern Disease Prevention

Take a look at the evolution of aspirin used in modern disease prevention to gain perspective on how more recent developments may affect your practice.

The use of aspirin for medical purposes started millennia ago in the form of willow leaves, but did not flourish until the 20th century, when researchers investigated and demonstrated its effectiveness as a primary prevention agent for cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Aspirin is well established for secondary CVD prevention, but recent research has changed the narrative, showing that the drug should not be used in routine primary prevention after all because of a lack of net benefit.

Scroll through the slides above to take a look at the evolution of aspirin used as medicine and gain perspective on how more recent developments may affect your practice.

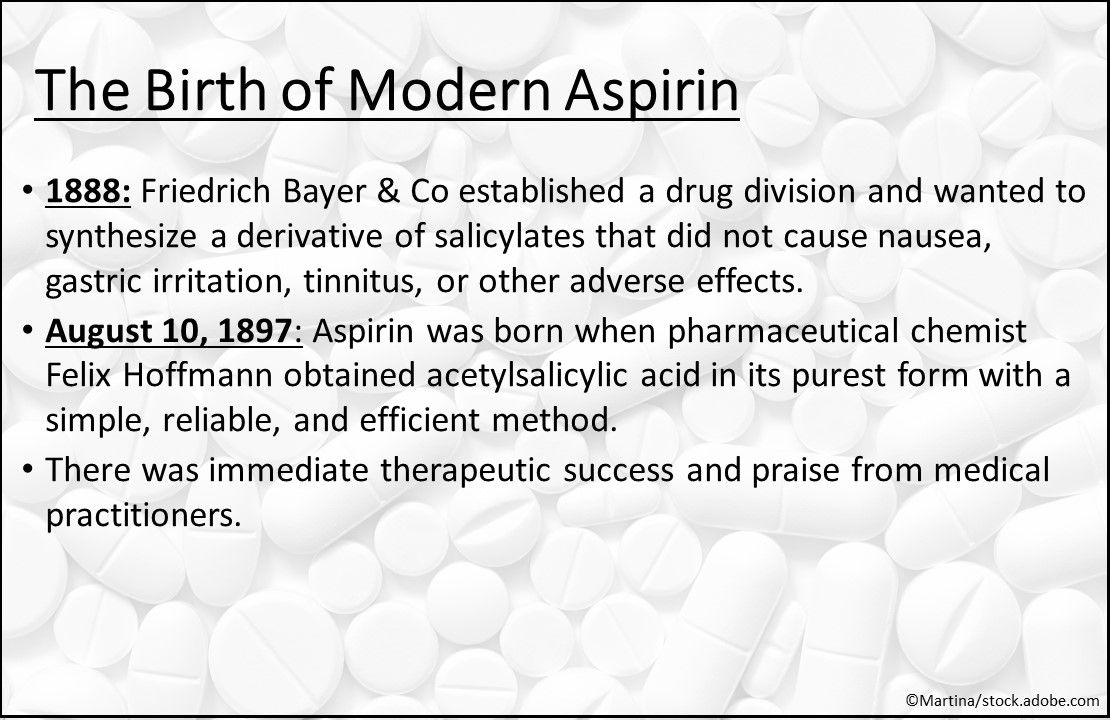

The birth of modern aspirin. In 1888, German dye manufacturer Friedrich Bayer & Co established a drug division and wanted to synthesize a derivative of salicylates that did not cause nausea, gastric irritation, tinnitus, or other adverse effects. Felix Hoffmann – a pharmaceutical chemist at Bayer – obtained acetylsalicylic acid in its purest form with a simple, reliable, and efficient method, and on August 10, 1897, aspirin was born. There was immediate therapeutic success and praise from medical practitioners. Bayer marketed aspirin as an analgesic, antipyretic, and anti-inflammatory agent, initially in a powder form and then in tablets in 1904. The first clinical studies were published in 1899.

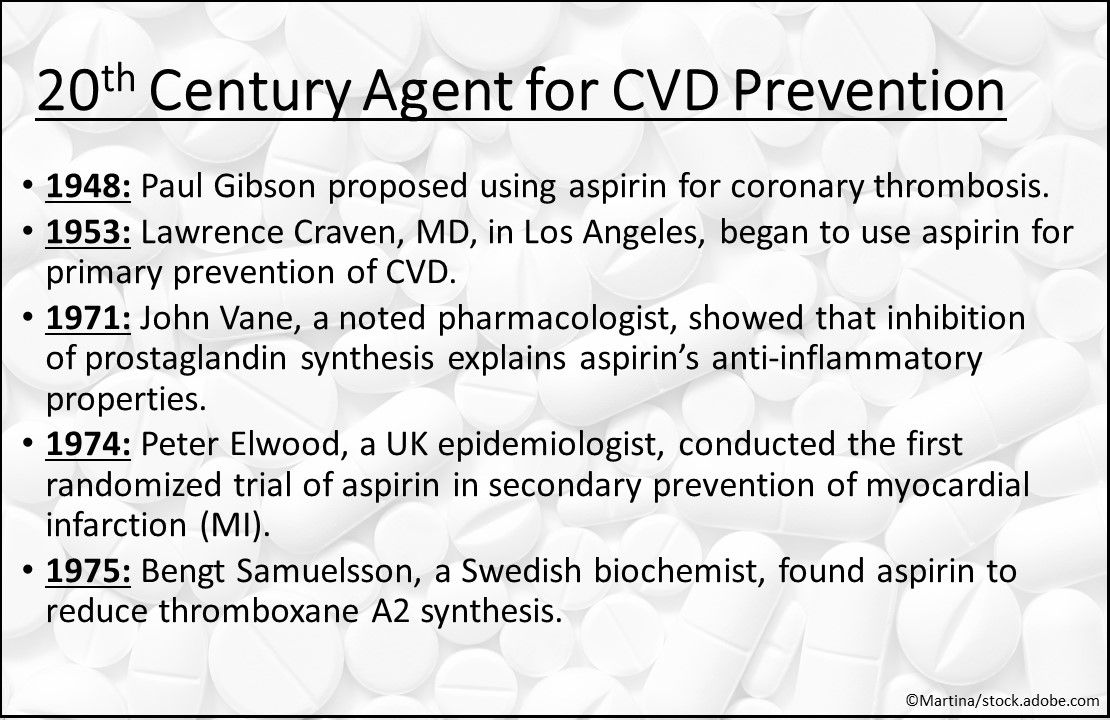

20th century agent for CVD prevention:

- In 1948, Paul Gibson proposed using salicylic acid for coronary thrombosis.

- In 1953, Lawrence Craven began to use aspirin for primary prevention of CVD.

- In 1971, John Vane showed that inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis explains aspirin’s anti-inflammatory properties.

- In 1974, Peter Elwood conducted the first randomized trial of aspirin in secondary prevention of MI.

- In 1975, Bengt Samuelsson found aspirin to reduce thromboxane A2 synthesis.

- In a 1978 trial, aspirin reduced the risk of continuing ischemic attacks, stroke, or death.

- In 1983, a VA study assessed prophylactic use of aspirin in men with unstable angina.

- In 1988, the ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) trial proved early aspirin treatment effective in reducing mortality from MI.

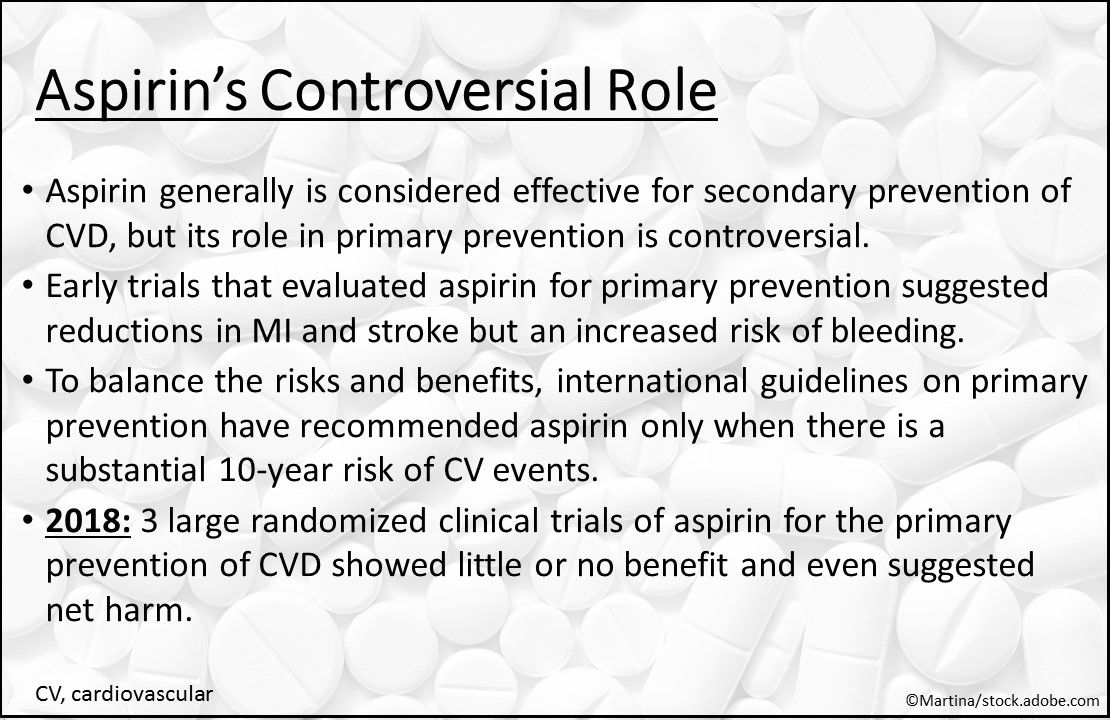

Aspirin’s primary prevention role gets controversial. Aspirin generally is considered effective for the secondary prevention of CVD, but the role it plays in primary prevention is controversial. Early trials that evaluated aspirin for primary prevention suggested reductions in MI and stroke but an increased risk of bleeding. To balance the risks and benefits, international guidelines on primary prevention have recommended aspirin only when there is a substantial 10-year risk of CV events. In 2018, 3 large randomized clinical trials of aspirin for the primary prevention of CVD showed little or no benefit and even suggested net harm.

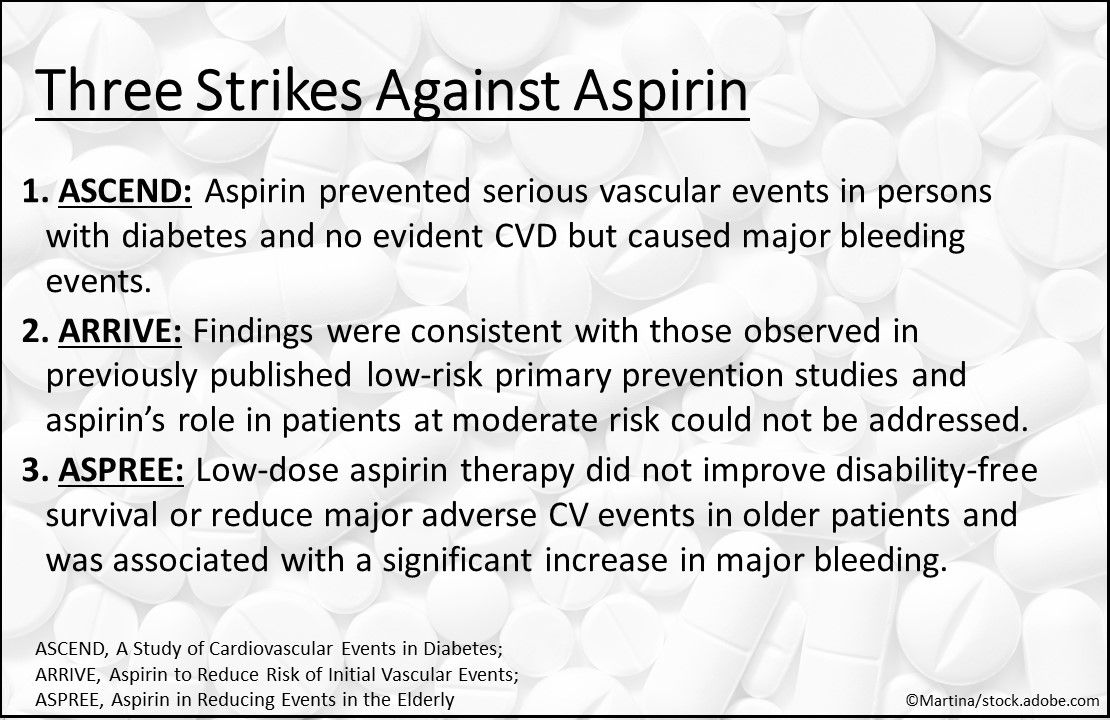

Three strikes and aspirin’s out. The benefits and risks of aspirin use for primary prevention of CVD in adults were evaluated in ASCEND, ARRIVE, and ASPREE. In ASCEND, aspirin prevented serious vascular events in persons with diabetes and no evident CVD but caused major bleeding events. In ARRIVE, the findings were consistent with those observed in previously published low-risk primary prevention studies and aspirin’s role in patients at moderate risk could not be addressed. In ASPREE, low-dose aspirin therapy did not improve disability-free survival or reduce major adverse CV events in older patients and was associated with a significant increase in major bleeding.

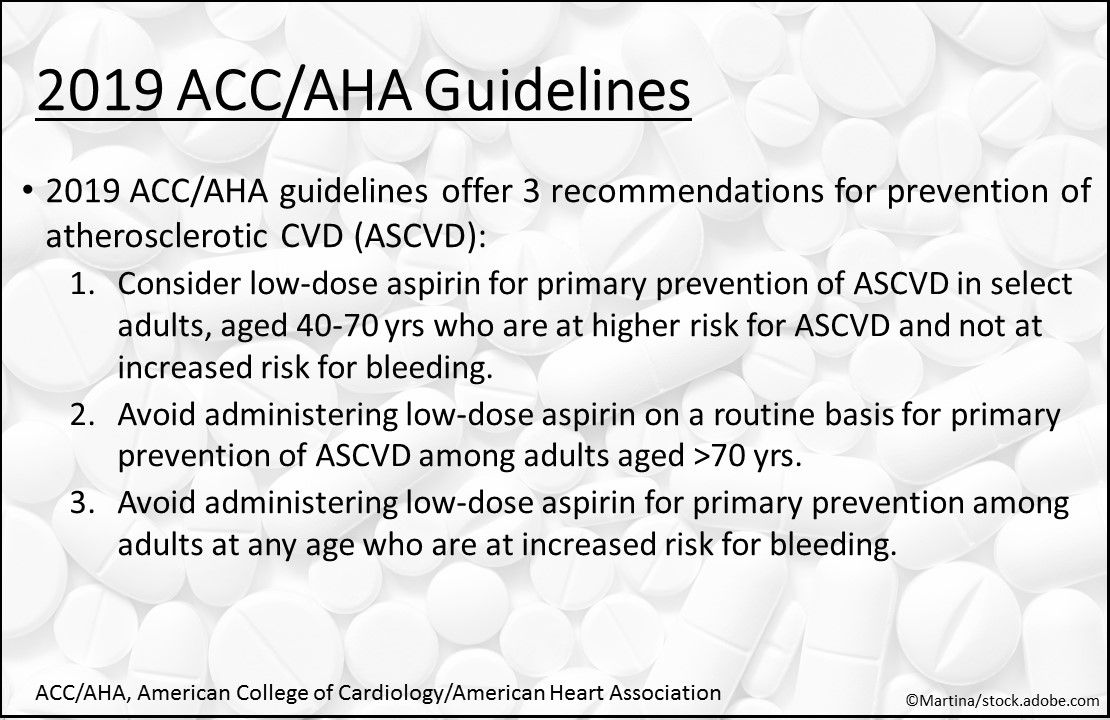

2019 ACC/AHA guideline on primary prevention. Based on meta-analysis and the 3 recent trials, the 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease offers these recommendations for ASCVD:

- Consider low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of ASCVD in select higher-risk ASCVD adults aged 40 to 70 years who are not at increased risk for bleeding.

- Avoid administering low-dose aspirin on a routine basis for primary prevention of ASCVD among adults aged >70 years.

- Avoid administering low-dose aspirin for primary prevention among adults at any age who are at increased risk for bleeding.

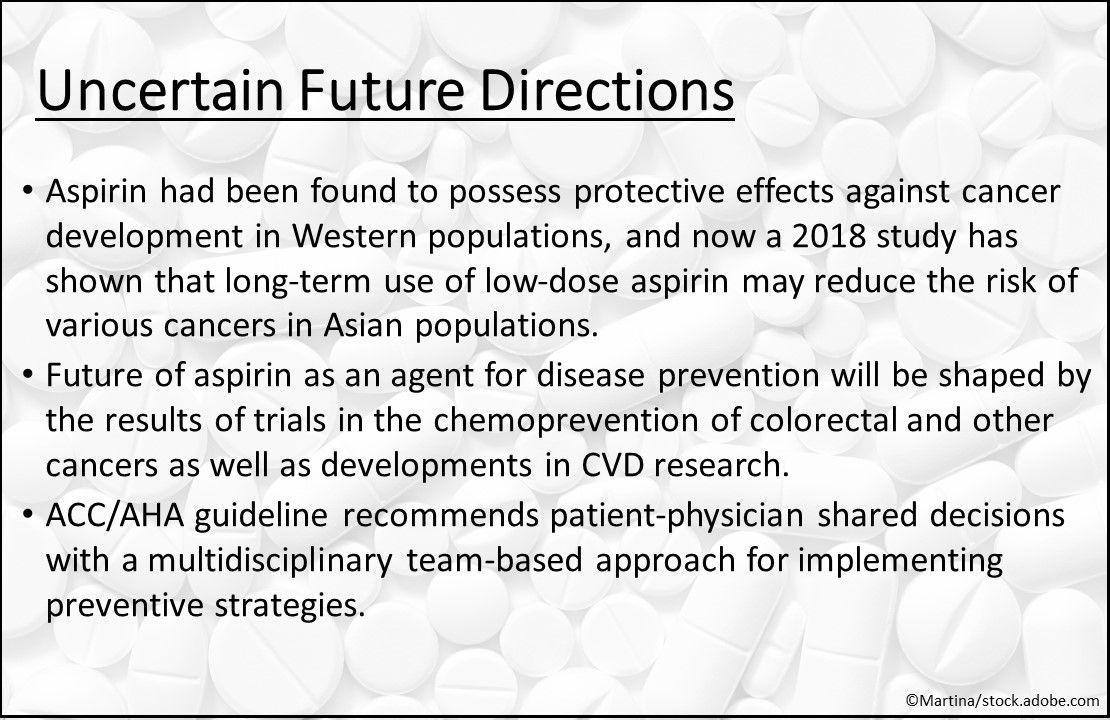

Uncertain future directions. As the use of aspirin for prevention of CV and cerebrovascular diseases has come into question, the drug has been found to possess protective effects against cancer development in Western populations. A 2018 study demonstrated that longâterm use of lowâdose aspirin may reduce the risk of various cancers, but not breast cancer, in Asian populations. The future of aspirin as an agent for disease prevention will be shaped by the results of trials in the chemoprevention of colorectal and other cancers as well as developments in CVD research. Meanwhile, for CVD, the ACC/AHA guideline recommends patient-physician shared decisions with a multidisciplinary team-based approach for implementing preventive strategies.

Want a deeper history of aspirin? Check out Aspirin: A Look Back at Its History.

Stay in touch with Patient Care® Online:

- Subscribe to our Newsletter

- Like us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Write or Blog for Patient Care® Online