© 2025 MJH Life Sciences™ , Patient Care Online – Primary Care News and Clinical Resources. All rights reserved.

Chronic Migraine: Why we Get it Wrong, Why it Matters

Episodic or chronic? Distinguishing between the 2 types of migraine is essential to ensure optimal treatment. Meet Abigail and Martin. Who has which headache?

Migraine is a common, painful and disabling neurologic disorder. Over the past decade there has been a push to divide migraine into two forms: episodic and chronic. But the actual definitions remain confusing, perhaps to all but the ~500 board-certified Headache Medicine specialists in the United States. Meet Martin and Abigail, 2 cases that help illustrate this widespread confusion.

Martin, age 66 years, has had migraine headaches for 40 years. He averages 6 headaches a month with typical migrainous features such as moderate-to-severe pain, nausea, and light and sound sensitivity. Abigail is 22-years-old and began having headaches only 4 months ago. She gets 8 migraines monthly, along with 10 mild-to moderate band-like headaches without migrainous features. Who has chronic migraine (CM)? Martin? Abigail? Both? Neither?

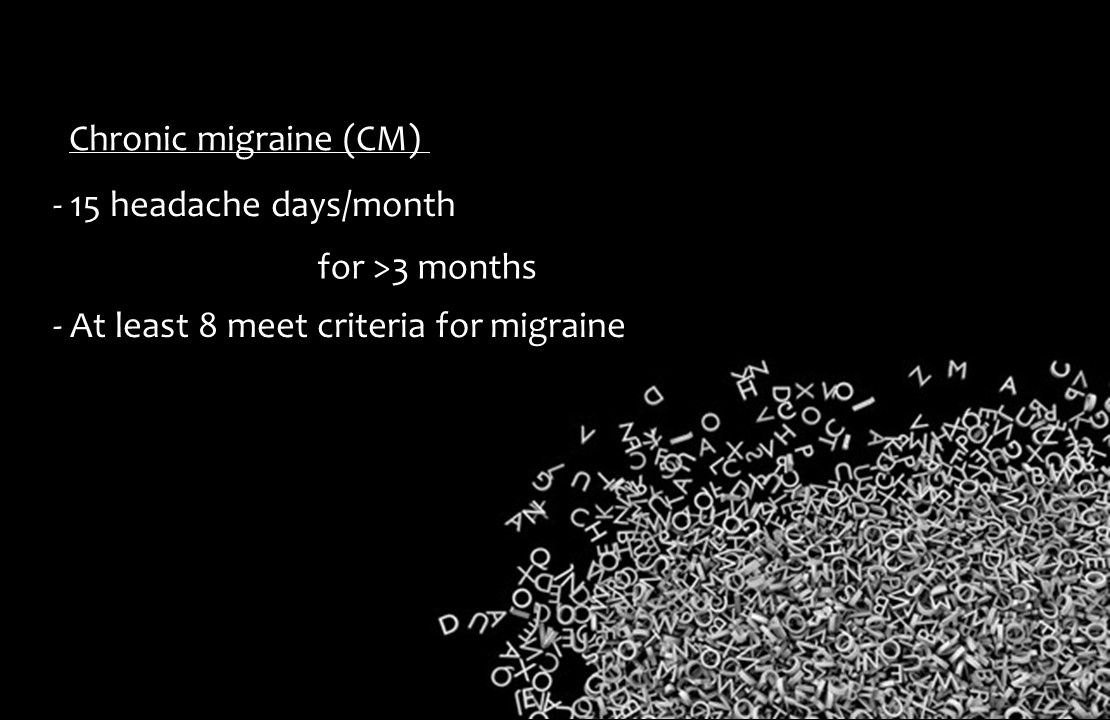

Although EM is far more common than CM, 5% of persons with migraine live at the very frequent end of the monthly headache day spectrum. Over the years this frequent headache pattern was variably termed chronic mixed headache,transformed migraine, and chronic daily headache, before the moniker chronic migraine was settled upon. Regardless of its name, what we now call CM per International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-III, section 1.3) is defined as 15 or more headache days per month, for more than 3 months, of which at least eight headaches fulfill criteria for migraine. CM is felt to represent a more aggressive and disabling form of migraine.

The dividing line of 15 headache days per month may seem arbitrary (other than dividing the month in half) and certainly one may quibble with how much different 12 or 13 headache days per month are compared to say, 16. Additionally, most CM patients will cycle over time between high frequency EM (8 or more but less than 15 headache days/month) and CM.

The important point is that in general, CM patients are worse off than EM in several important ways, including an increased tendency for depression and anxiety, higher body mass index, and greater difficulty with employment and thus lower socioeconomic status. CM patients utilize heath care resources to a greater degree than EM patients, and are more likely to have been victims of physical, sexual, emotional abuse or neglect.

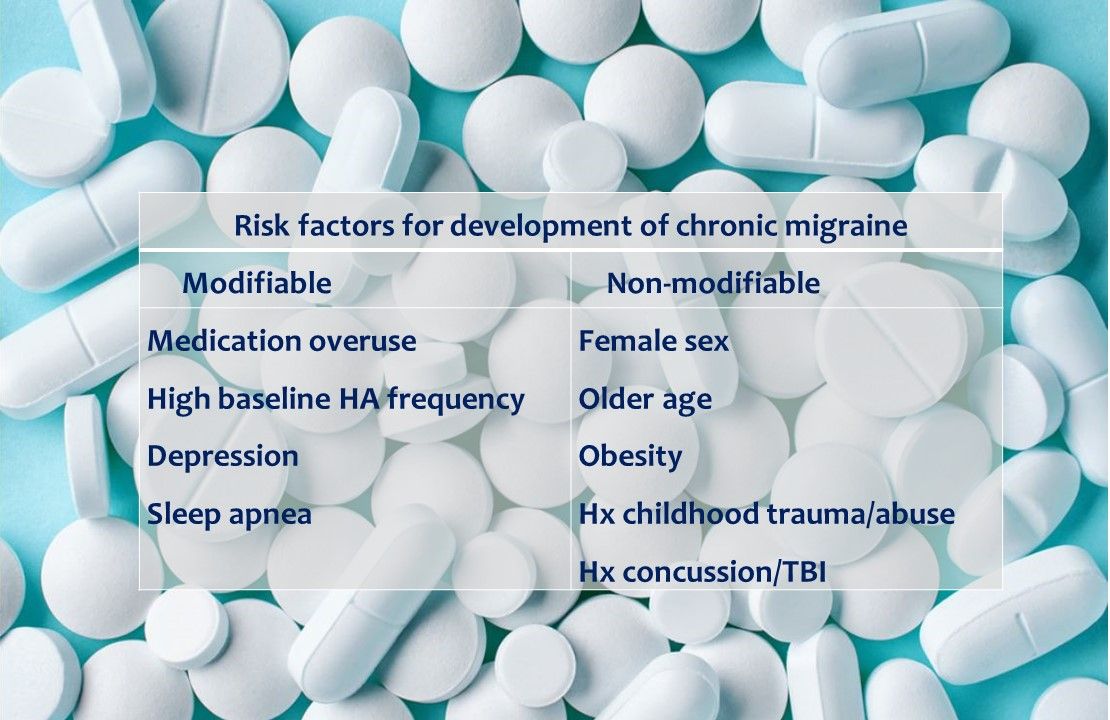

There are multiple risk factors for progression from EM to CM. Medication overuse (MO), which can produce medication overuse headache (MOH) is a common and important one. Use of simple analgesics on 15 or more days per month, or triptans, opioids, ergot alkaloids, or combination analgesics on 10 or days per month constitutes MO. Additionally, use of caffeine at greater than 200mg/day increases risk of MOH.

Principles of CM treatment overlap with migraine treatment in general, with a few notable distinctions. Nonpharmacologic interventions are important and likely underutilized. An understanding of risk factors for CM (and conversion of EM to CM), as well as a detailed patient history should guide these interventions. Maintenance of a daily schedule, frequent exercise, adequate hydration, and a healthy diet apply to nearly all CM patients. Certain vitamins and supplements shown to be effective in EM have not been systematically studied in CM. Weight loss counseling in overweight and obese individuals with CM is good practice.

Screening for childhood trauma and referral to a trauma specialist is essential for those with a positive history. Cognitive behavioral therapy, relaxation techniques and biofeedback are useful in CM sufferers, particularly those with comorbid anxiety. Risk factors for CM in children and adolescents appear similar to those for adults.

While not every EM patient needs daily therapy, virtually every person with CM should be offered preventive treatment, with the goal of reducing the number of headache days per month, lessening the severity of pain and associated symptoms, decreasing acute medication usage, and decreasing or eliminating functional disability. While many preventive agents have been tested in EM, few have in CM. Strong evidence for efficacy in CM prevention exists for topiramate, onobotulinumtoxinA (Botox) and the four calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP) blocking monoclonal antibodies erenumab (Aimovig), fremanezumab (Ajovy), galcanezumab (Emgality) and eptinezumab.

So back to Martin and Abigail. Applying ICHD-3 criteria, we can conclude that although Martin has had migraines a long time (there is chronicity to his disorder), he does not have CM, but rather EM. Abigail, on the other hand, has had a brief history of headache, but at 15 or more total headache days a month (8 migraine and 10 tension-type headaches) for more than three months, her condition fulfills criteria for CM.

While Martin may respond to acute therapy (such as triptans or NSAIDs) alone, Abigail needs more aggressive care. She should be told of her diagnosis (CM, rather than simply migraine) and started on a preventive agent specifically studied in CM. She should receive migraine-specific acute treatment, along with tips for lifestyle modification. If she fails to respond, referral to a neurologist or dedicated headache center is warranted.

Understanding the definitions of and difference between EM and CM will aid in triaging care, which in turn should lead to improved patient outcomes.

Selected Reading

Diener H.C et al. Chronic migraine - Classification, characteristics and treatment. Nature Rev Neurol. 2012;8:162-71.

Wiendels, N.J. et al. Chronic frequent headache in the general population: comorbidity and

quality of life. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:1443–1450.

Stewart WF, Wood GC et al. Employment and work impact of chronic migraine and episodic migraine. J. Occup Environ Med. 2010;52:8-14.

D’Amico, D. et al. Quality of life and disability in primary chronic daily headaches. Neurol Sci. 2003;24(Suppl. 2):S97–S100.