© 2025 MJH Life Sciences™ , Patient Care Online – Primary Care News and Clinical Resources. All rights reserved.

Depression Presents Diagnostic Challenges in Primary Care

Highlights of an evidence-based review offer practical guidance for effective depression screening and assessment strategies for primary care physicians.

Globally, >300 million people have depression, and the prevalence rose by 18.4% over a recent 10-year span. In the US, depression now accounts for >8 million doctor visits each year, and more than half of these visits are in the primary care setting.

As patients’ needs for effective diagnosis and treatment increase, so do the challenges primary care physicians (PCPs) face in meeting them. To help guide PCPs in recognition and management of depression, Erin K Ferenchick, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, and colleagues earlier this year provided practical evidence-based guidance in a 2-part review published in The BMJ.

In the slides above, we give details on part 1, which outlined an approach and recommendations to depression screening and diagnosis in primary care.

Diversity complicates diagnosis. The heterogeneity of depression presents a significant diagnostic challenge. Depression is associated with genetic, environmental, biological, cultural, and psychological factors. The disorder often begins in the second or third decade of life, but can occur at any age. Prevalence rates vary by age and peak in older adulthood. Patterns of depression often differ within racial and ethnic minorities. Researchers recommend general screening to identify depression in primary care, as long as adequate systems for treatment and follow-up are in place.

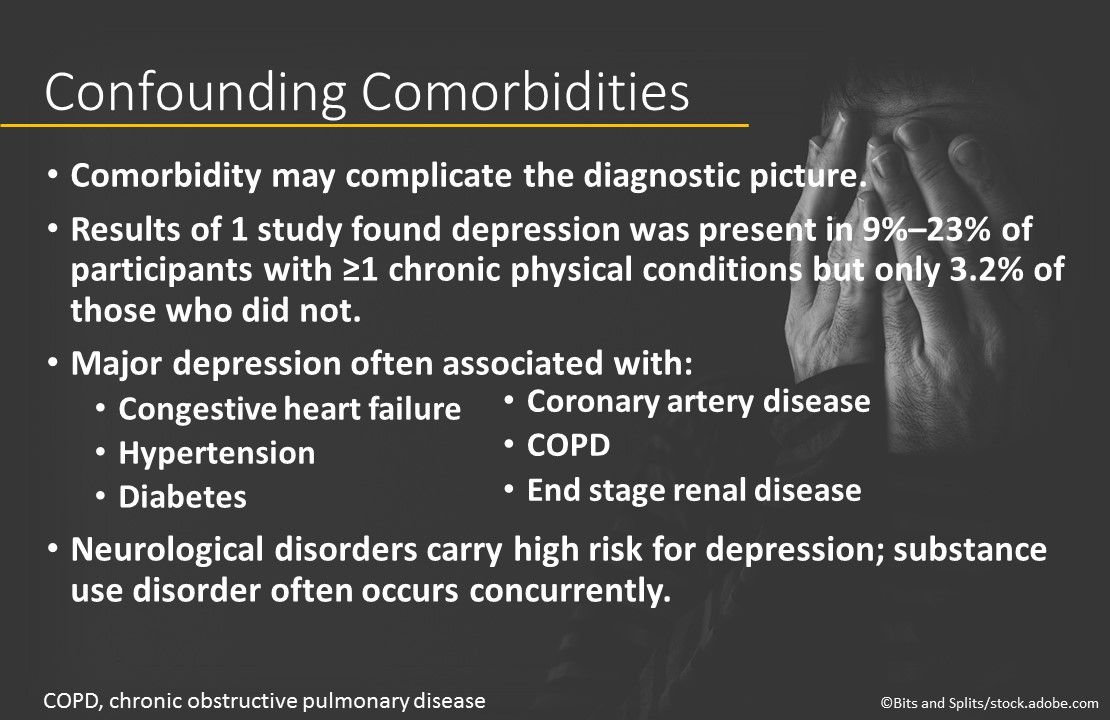

Confounding comorbidities. Recognition of depression in primary care is further complicated by concurrent comorbidities. In a population-based study, depression was present in 9% to 23% of persons who had ≥1 chronic physical conditions but in only 3.2% of those who did not. In another large study, 12-month prevalence of major depression by chronic conditions was: congestive heart failure, 7.9%; hypertension, 8.0%; diabetes, 9.3%; coronary artery disease, 9.3%; COPD, 15.4%; and end stage renal disease, 17.0%. Neurological disorders carry a high risk, and substance use disorder often occurs concurrently.

The problem with somatic complaints. Some patients present with the classic symptoms of depressed mood, but others report nonspecific symptoms or only somatic complaints, reducing the likelihood of a correct diagnosis. The authors recommend creating a composite profile that includes common somatic complaints-eg, changes in appetite, lack of energy, and sleep disturbance-depressed mood, and the presence of known risk factors for depression-eg, previous episode, history of other mental illness, history of substance use, and family history of depression or suicide.

Support for depression screening by PCPs. Support for depression screening in primary care comes from the USPSTF (general adult population, including pregnant and postpartum women), the AAFP and ACPM (general adult population), and the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (if suspected based on risk factors or presentation). Current evidence suggests screening does not improve care quality and outcomes unless PCPs also provide accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and appropriate follow-up.

Top tools of the trade. Several instruments may help PCPs identify patients with depression, but the consensus choice for validity, reliability, and brevity is the PHQ, including 2-item (PHQ-2) and 9-item (PHQ-9) versions. Studies have shown the PHQ-2 and other ultra-short screening instruments to be an efficient option for busy PCPs, but many physicians use a 2-step process: First screening with the PHQ-2 and then confirming with the PHQ-9. Researchers suggested using screening instruments to enhance rather than replace the clinical interview.

Classification systems for assessment. If screening is positive, further diagnostic assessment is needed. The DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association) is a widely used classification system along with the ICD-11, developed by the World Health Organization. Both are recommended for diagnosis of depression in the primary care setting.

Stay in touch with Patient Care® Online:

→Subscribe to ourNewsletter →Like us on Facebook →Follow us on Twitter →Write or Blog for Patient Care® Online→Follow us on LinkedIn